(A version of this ran June 15) On this Father’s Day, please permit a look at some political lessons I learned from my father.

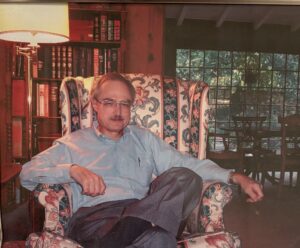

Haywood H. Hillyer III, who died 15 years ago this spring, was one of those political volunteer leaders who saw his involvement as a civic duty rather than as a form of personal advancement.

One of 100 young leaders from across the country invited to William F. Buckley’s Connecticut estate to found the Young Americans for Freedom group in 1960, founder of a campus conservative newspaper at Tulane University that featured writings from numerous future state and national political leaders and judges, a one-term member of the local Republican Parish Executive Committee and quarter-century member of the Republican State Central Committee, Dad ended by serving more than four years as Louisiana’s (sole) Republican National Committeeman.

In that last role, Dad worked assiduously to keep neo-Nazi David Duke from seizing the formal, organizational reins of the Louisiana Republican Party when Duke’s political career was ascendant – including one incident when Dad physically interposed his body between Duke and the podium when Duke tried to seize control of a state political convention.

Through it all, Dad was one of that rare breed who never asked for anything in return for his volunteer work: no business, no favors for his friends, no patronage fiefdoms. Instead, to his law firm’s displeasure, he lost countless billable hours while instead working to advance the principles in which he believed.

Almost always on the conservative side of intra-party disputes, Dad nevertheless was trusted by all sides as being scrupulously fair. The state central committee’s job is to set party rules – and as political insiders understand, sometimes the rules themselves can, in backdoor ways, favor one side or another.

I watched in numerous SCC meetings when anger rose as matters reached impasses, only for my father to rise and, in quiet tones, propose and explain a workable solution. Almost invariably, the emotional temperature would drop and my dad’s proposal would be adopted. It was for good reason that in one of my father’s re-election races, longtime New Orleans GOP leader Charlie Dunbar mailed an endorsement letter whose first line, taken from the old E.F. Hutton commercial, was this: “When Haywood Hillyer talks, people listen.”

One major key to his credibility (in addition to the force of his logic) was that everyone knew that while Dad considered politics to involve fierce competition, he considered it a contest of honor rather than a blood sport. Unless and until an individual showed otherwise, Dad assumed everyone was acting in good faith and he therefore showed respect to those with whom he disagreed. (He also refused to ascribe blame to a whole group if individual members of that group “dealt dirty.”) Respect, in return, was afforded to him.

While Dad was as interested in practical results as anyone – and usually pretty good at getting them – he still, and always, saw political action as an expression of idealism. Yet he had the humility to avoid absolutism: Compromise, he believed, could be thoughtful and principled rather than craven. His job was to work like heck to advance his beliefs, and then to take the most favorable achievable result and move on.

Meanwhile, one of Dad’s deep desires was to de-racialize politics. He told me of when he was at his boarding school up East, not yet 17 years old, when the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education ruled that school segregation was unconstitutional. One of his snooty teachers, knowing Dad was a southerner, assumed Dad would be angered by the decision. Dad, indignant at the teacher’s assumption, said he told the teacher: “I don’t know the legal ins and outs, but I see no reason why it hurts a white boy or a black boy to sit next to each other while they learn to read.”

Several years later, as a traditional jazz aficionado, Dad regularly ignored segregation laws by going in the back rooms and back alleys with veteran black jazz musicians during their between-set breaks so he could hear their four-decade-old stories of the dawn of the Jazz Age. Those experiences guided him as he tried diligently (but, alas, without much success) to recruit black voters to the Republican side while trying to steer the party’s substance and rhetoric away from anything interpretable as featuring racial undertones.

Among the many political lessons I learned from Dad, then, were these: that politics at heart should maintain a sense of idealism, that honor and trust are crucial, that political opponents need not be personal enemies, and that appeals to racial animus – and indeed all forms of bigotry – have no valid place in American life.

Meanwhile, Happy Father’s Day, one and all. [END}

[The link to the published version is here.]